The Covid-19 Whistleblowers

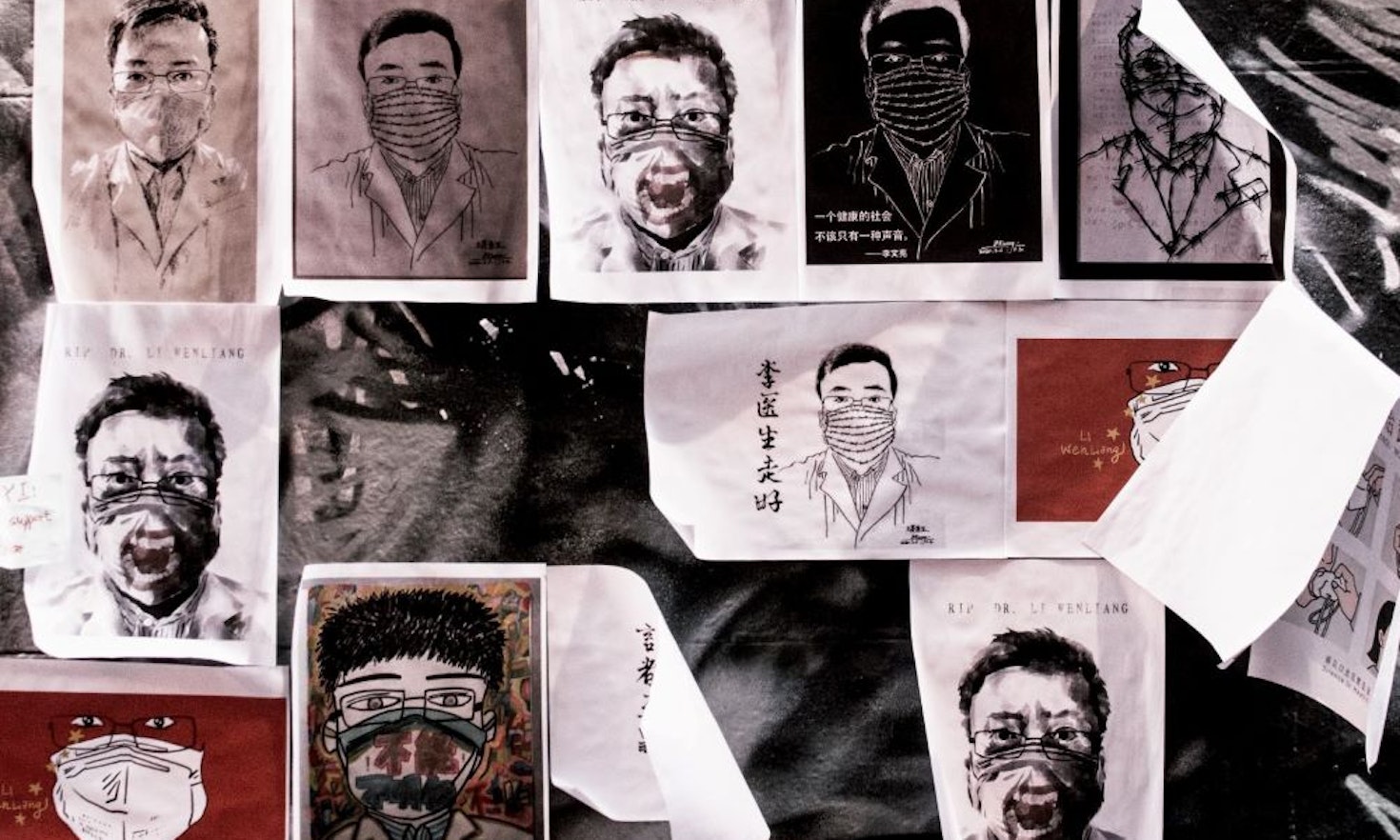

Before the world moved into the unknown direction of what the WHO classifies as a pandemic, Li Wenliang, a doctor in Wuhan, had already warned authorities of an extremely contagious disease. Any testimony or interview with him was silenced. The director of the hospital where Wenliang worked was also reprimanded for having warned of the danger of this new disease that was taking the lives of health workers and was spreading without anyone really knowing how and why. As what had also happened in the case of the (in)famous/well-known Edward Snowden, all information was repressed until the situation exploded by itself.

The media echoed that case, and any loophole in these statements on the internet were recovered by users, and thus facilitated other States to have testimonies about what had previously happened. Unfortunately, we discovered the existence of this virus and its fatal consequences long before we knew about the doctor’s public complaint.

In these terms, no one is surprised that in countries where freedom of expression was already “somewhat limited” before the pandemic, that these circumstances occurred and it’s even less surprising now that we know about the serious misprints in the actual number of deaths that were reported as relatively low in a country with as high a population as China.

But the question that may arise is: what would happen in countries like Italy and Spain if irregularities in crisis management were reported? The answer is quite complicated. Italy has a law for its whistleblowers in the private sector who witness non-compliance with the legislation in their work, also, by establishing whistleblowing channels, that can determine the company’s responsibility. And for the public sector, the law has established limits for the people who can report information, with the main goal of confronting corruption.

In Spain, the case is different since there are different rules in each of the country’s Autonomous Communities and the object is different in each community. However, most rules apply for the public sector, and they establish protection measures such as voluntary leave, change of position within the workplace or the possibility of receiving free legal advice. All this, “in spite of” three (so far unsuccessful) attempts of drafting a state law to protect the whistleblowers pointing to cases of corruption. In other words, there is no specific national law for whistleblowers, but “there is something” which can drive decisions.

Despite the differences, both countries have an obligation to transpose the Directive 2019/1037 on the protection of people who report infringements of the Union Law. This means that both, Italy and Spain, must legislate in favour of people who denounce, especially if that accusation prevents tragedies like the ones we are witnessing.

According to the Directive, the recitals include the importance of protecting those who are aware of threats against the public interest, that may occur within a public or private organisation. Protecting those who blow the whistle and disseminate such information is, for the EU, one of the challenges to still be met, since the first recommendations to its states were drafted in 2014. This challenge becomes more acute when we have different states fighting the same problem, in completely different ways and with a global economy about to go through its second crisis which it was almost recovering from and which puts public money and EU funding on the table to fight this virus.

Pandemic and corruption: united hand in hand

Going back to the previous question, and using the example of a doctor who would publicly denounce the spread of the virus, but this time in Europe., we understand that the doctor would be covered under this new Directive, since the minimum standards include infringements in the field of public health. In fact, they would also be protected in extreme cases where there is direct contact with the media, due to the fact that there is an imminent danger, as we have seen regarding the number of victims that the virus has claimed.

And what happens if irregularities are discovered in the public procurement? Would the whistleblower have the established whistleblowing channels and the guarantees included in the Directive? In fact, in view of this crisis, new concerns have arisen, especially in the area of public procurement – which is also included in the reportable infringements of the Directive – because, in view of the rapid and effective response of the states, corrupt behaviour may also appear in favour of certain companies that may provide, albeit defective, services in sanitary materials.

In general, the idea is that this serious health crisis should not benefit any sector, nor should it be a facilitator of corruption. We have chosen to expose this because in different countries the governments have been accused of taking advantage of this situation to commit acts of corruption. However, these are still assumptions, and nothing has been investigated. In general terms, this situation can facilitate corruption acts, and can be attractive for the guarantors of publics goods to succumb to corruption.

Finally, it was not easy to be a whistleblower before the outbreak of Covid-19, nor it is now in times of “every man for himself” and with such a limitation of certain rights. Therefore, we need to protect those who blow the whistle more than ever.

| Cristina Fernández González is a criminologist and researcher in training at the Research Center for Global Governance (University of Salamanca). Currently, she is investigating about corruption reporters (whistleblowers) and effective protection measures. Her main field of research is anti-corruption measures and integrity policies. In her free time, she loves being with her friends and going to the gym. |

Citation

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license except for third-party materials or where otherwise noted.