Fake It till You Make It: Inventing the Neoliberal Self

Neoliberalism is not simply a way of governing economies or states. It engineers a new kind of subject, the ‘entrepreneur of the self’, by promoting neoconservative ideals and values like autonomy, personal growth, self-reliance, and self-government. The neoliberal self is constructed as both a brave risk-taker and as permanently precarious. The advancement of neoliberal values and goals is particularly explicit in reality competition shows like Survivor and Squid Game, whose ruthless elimination logic divides the world into ‘winners’ and ‘losers’.

The emergence of a ‘neoliberal subjectivity’ has been the subject of various genre studies, including those of the 'multiple film' and 'puzzle films', whose convoluted narrative structure can be seen as a symptomatic manifestation of cinematic neoliberal subjectivity: they present us with a utopian imagination of multiple alternative worlds but in reality demonstrate that there is no alternative to capitalism. While many scholars trace the neoliberal subject as an ‘entrepreneur of the self’ back to the classical noir subject, there are also moderately optimistic studies that reclaim the potential of anti-neoliberal cinema to envision new forms of solidarity and to empower viewers.

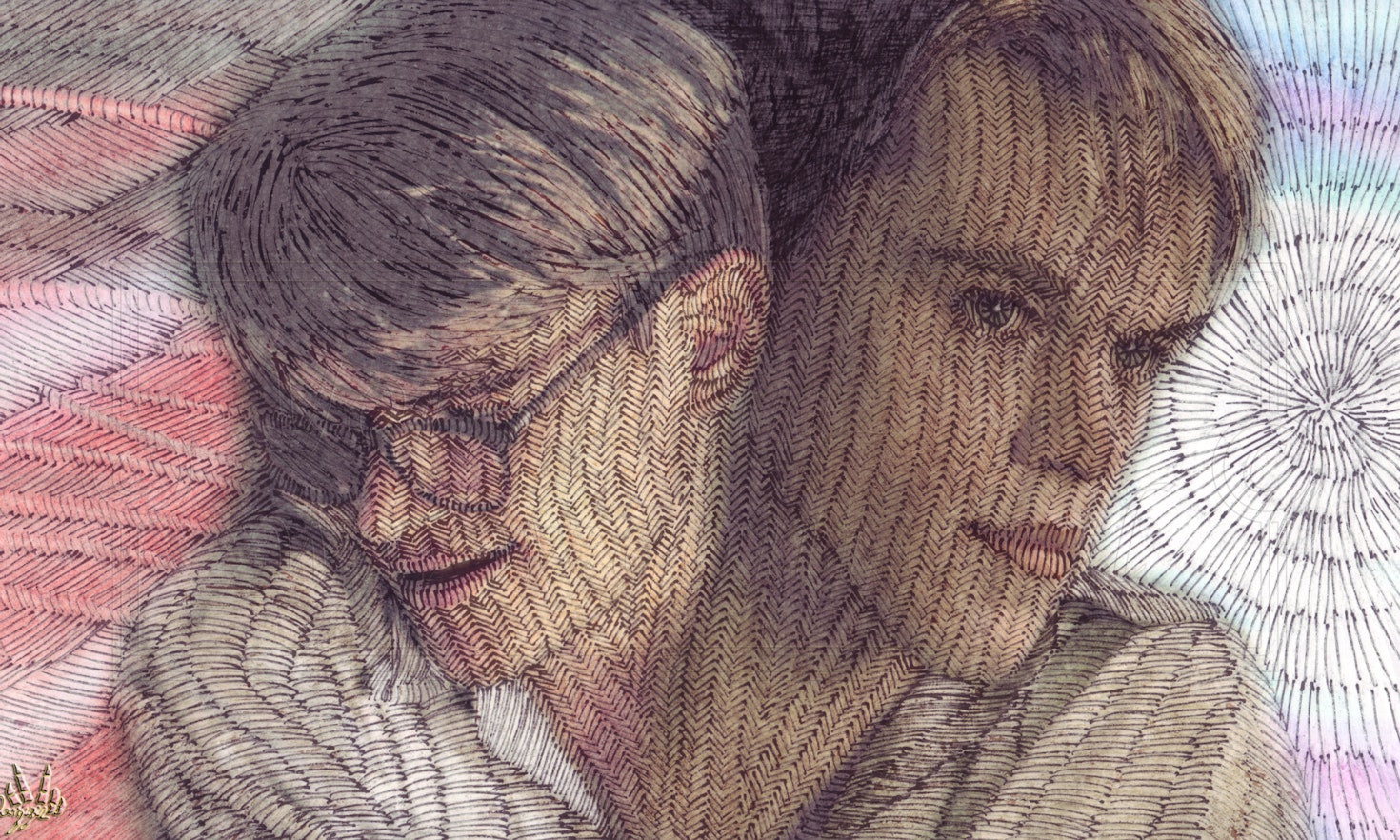

American cultural theorist Lauren Berlant has identified 'cruel optimism' as the dominant strategy of adjustment to life under neoliberalism. To suffer from ‘cruel optimism’ is to cling to the fantasy of the ‘good life’ despite evidence that this form of attachment is harmful, giving rise to self-deception and delusion. One figure that has attained a celebrity status, both on and off screen, and that embodies the new pathologies of self-deception and delusion that neoliberalism has given rise to, is the impostor, in which neoliberal ideas of individual self-monitoring and self-reliance intersect. The psychological pressure of producing and sustaining oneself as the ideal self-managing neoliberal subject is reflected in the growing number of con artists, grifters, hustlers and impostors populating contemporary cinema, pursuing with deranged determination the ‘good life’ straight down the line, where distinctions between fact and fiction, reality and fantasy, disappear.

We have always been attracted to stories about con artists and grifters trying to game the system because of how relatable they are. This was one of the reasons why audiences found themselves drawn to morally ambivalent noir protagonists like Walter Neff (Double Indemnity, 1944), an insurance salesman who, lured by a femme fatale, helps her devise a plan to murder her husband and receive a payout from the insurance company. The con artist is “the avatar for the average person who is maybe too afraid or has enough morality not to experiment with this type of behavior.” Many agree that transformations of the welfare state and the labor market (the restriction of state influence on the economy, the deregulation of capital markets, the lowering of trade barriers, the elimination of price controls, the introduction of austerity measures, the rise of the gig economy) have initiated the golden age of the con artist as the omnipresence of the impostor in contemporary cultural production testifies - from Time Out (2001), Faultless (2016) and Parasite (2019), to The Origin of Evil (2022), The Dropout (2022), and Inventing Anna (2022). In the words of Jessica Pressler, whose article in New York magazine was the inspiration for Inventing Anna, what’s satisfying about these types of stories is that "when somebody games the system, you see that there is a system."

The neoliberal ‘entrepreneur of the self’, whose cinematic manifestation is the impostor/con artist, swings between two affective poles: denial and delusion. What if you lose your job but continue to live as if nothing happened? This is the premise of Time Out, in which a company executive unable to adapt to neoliberal imperatives of work retreats into a life of napping, spacing out, wandering in hotel lobbies, parking lots, and office waiting areas. The fictious job he invents (to maintain the illusion of being employed) as an altruistic UN bureaucrat in charge of Third World development, the Ponzi scheme he orchestrates to extract money from old friends, and the smuggling operation of counterfeit goods he joins, link his artful dissimulation with the "false promises of a faltering European economic order." At the opposite extreme are films about impostors who do not simply deny reality but actively construct a fantasy to replace the reality they find unsatisfactory (e.g., Faultless, The Origin of Evil). A poignant scene in The Dropout, in which Elizabeth Holmes stares at herself in the mirror as she rehearses a speech she is about to give to her company’s board of directors, repeating in a robotic voice “This will be a momentous leap…,” captures perfectly what it means to become a self-managing neoliberal subject.

The experience of women is central to theorizing a neoliberal regime of power that derives its profits from the kind of skills often associated with femininity—flexibility and adaptability. In Gendering the Recession: Media and Culture in the Age of Austerity (2014), Diane Negra and Yvonne Tasker criticize post-feminist culture’s tendency to hold individual women rather than structures of gender hierarchy responsible for gendered inequality and injustice. Indeed, gender plays a crucial role in film and tv representations of the self-managing neoliberal subject. Compare male-centered films about financial fraud and con artistry like The Big Short (2015), about the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and Dumb Money (2023), which chronicles the GameStop short squeeze of Jan 2021, with films and tv series centered on female protagonists like Faultless, The Origin of Evil, The Dropout, and Inventing Anna. The Big Short and Dumb Money, ensemble-driven biographical comedy-dramas, are plot-driven rather than exploring the individual psychology of their protagonists. Lauded as films about modern day class warfare, they require audiences to possess a certain level of expertise in finance, with the former famously featuring cameo appearances by celebrities explaining concepts like ‘subprime mortgages’ and ‘synthetic collateralized debt obligations.’ By contrast, female-centered films about con artists and impostors are framed as character studies: Inventing Anna spawned endless discussions of its protagonist’s mental condition (from antisocial personality disorder, through narcissistic personality disorder, to delusions of grandeur), while The Dropout attributed its protagonist’s imposterism to a sexual assault trauma (Holmes did testify she was sexually assaulted while she was at Stanford; in the series final episode the company’s legal advisor spells out the reasons for Holmes’ sociopathic lack of affect: it’s because Holmes was in denial about her assault, allegedly because her mother advised her to forget about it, that she was incapable of understanding that her fraudulent company is hurting real people).

Like these TV series, Faultless and The Origin of Evil, both featuring an unreliable narrator/femme fatale, a staple of film noir, focus on their impostor protagonists’ descent into lawlessness, delusion and derealization, and dedicate more time to the characters’ subjective experiences than to examining the social and economic structures that produce the delusions and obsessions they suffer from. These films are more interested in ethical and moral questions than in the social and economic implications of neoliberalism or in the politics of class. In Faultless the unemployed Constance returns to her hometown hoping to get a job at the small real estate company where she used to work before moving to Paris. When her boss hires the much younger Audrey instead, Constance begins stalking Audrey and feigns to be an apartment hunter to infiltrate her life. She then breaks into her house, showers in her bathroom and sleeps in her bed. Her intention: to get rid of her. Critics saw the film as "dabbling in Brian De Palma territory (stake-outs, break-ins and voyeurism)", and Constance as nothing more than "a woman on the verge of either a nervous breakdown or a multiple homicide," thus failing to acknowledge the film’s commentary on the devastating psychological and emotional effects of precariousness. In The Origin of Evil Nathalie, on the verge of financial collapse, assumes another woman’s identity to infiltrate her bourgeois family. Nathalie’s performance is so convincing that she comes to believe she is the long-lost daughter of a wealthy businessman. Staying close to the character (through numerous close ups and reaction shots) the film presents itself as an anatomy of its protagonist’s fall into delusion. Similarly, The Dropout puts its protagonist’s psychological breakdown front and center, digging deeper and deeper into Holmes’s sociopathic tendencies.

On the one hand, the tendency of female-centered films to adopt a more intimate point of view on neoliberalism’s hustle culture by dissecting the psychological reasons and motivations of their impostor protagonists—especially when seen side by side with the broader social picture provided by films like The Big Short and Dumb Money—resurrects obsolete gendered distinctions between the ‘private’ and the ‘public’ sphere, coded as ‘female’ and ‘male’, respectively. And yet, by focusing on the affective aspects of the culture of grifting female-driven films are better positioned to help us rethink the ‘impostor syndrome’ as a public rather than a private feeling, as British sociologist Maddie Breeze urges us to do, by laying bare neoliberalism’s affective and social pathologies, neuroses, and phobias.

Citation

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license except for third-party materials or where otherwise noted.

Edipo siamo noi: Warum wir aufhören müssen, uns als Krönung der Schöpfung zu betrachten

Geo-economics of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

Bartosz Stefan Michalski

Bartosz Stefan Michalski

UNESCO-Zukünftebildung: Von der Vorstellungskraft zur gemeinsamen Gestaltung

Roland Benedikter

Roland Benedikter