Visegrad countries U-turn on migration: fresh impetus for EU asylum policy?

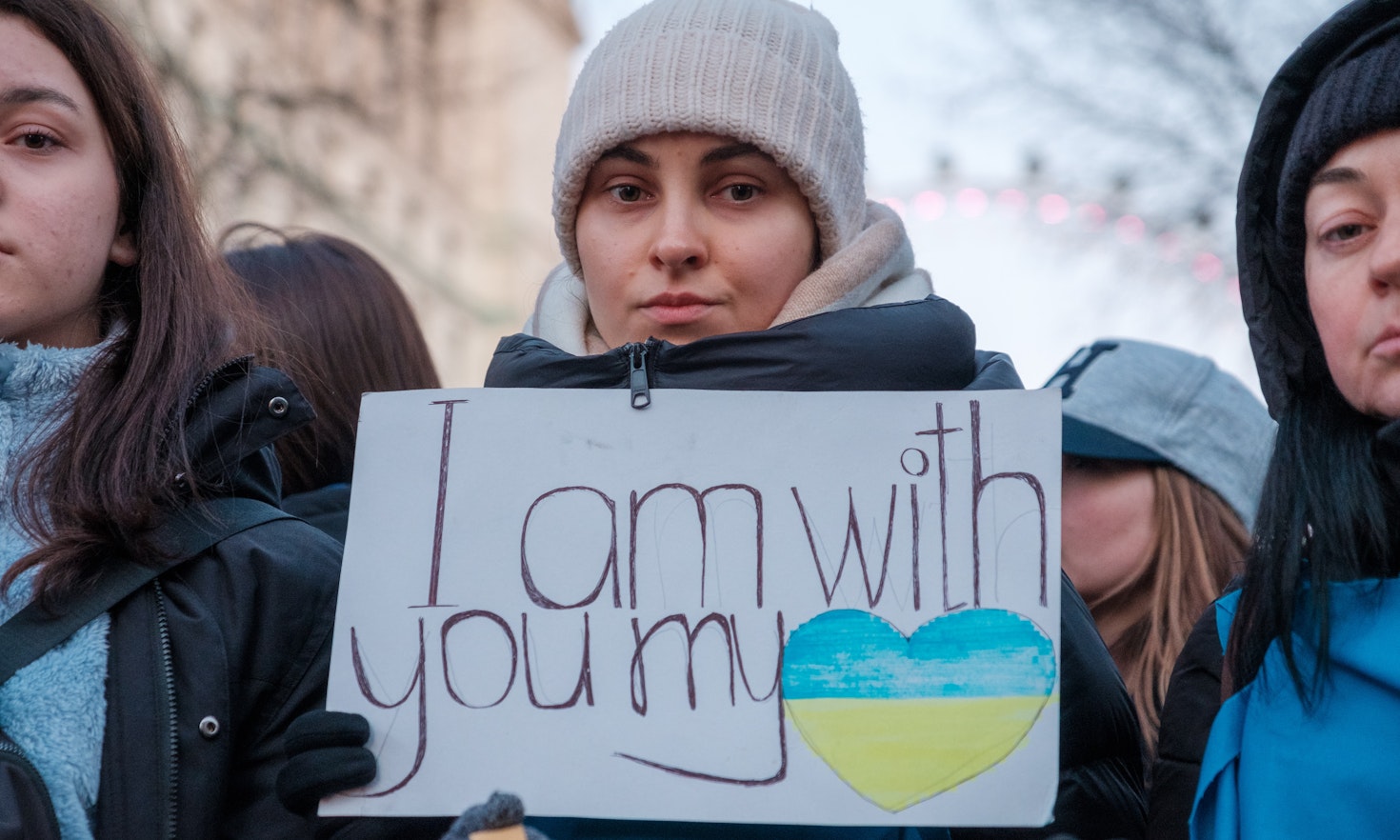

Ten million people living in Ukraine have fled to the European Union since the Russian invasion. Legally speaking, there is little doubt that these persons can be classified as asylum-seekers. So far, the main destination countries have been those which border Ukraine: Poland, Slovakia, Romania and Hungary. Poland, Slovakia and Hungary are members of the so-called Visegrad Group, also commonly known as V4 which is made up by 4 members: the aforementioned as well as the Czech Republic. The sudden mass influx of asylum-seekers is a test for the V4 and is disrupting the approach to migration and solidarity they have been pursuing so far, to such an extent that about it can even be described as a veritable – and somehow unexpected – “U-turn”.

Limited solidarity, state-centered decision making, and a rejection of the EU’s Pact on Migration and Asylum

Before the war in Ukraine, the V4’s main aims in the field of migration and asylum were to limit the arrival of asylum seekers as much as possible. This was part of a nationalist political rhetoric, embedded with many references to the Christian faith which characterizes all four members, notably Hungary. At EU policy level, the V4 rejected the EU’s mandatory relocation scheme which was based on the compulsory quotas set by the European Commission in 2015. This was in response to migrant boat crises in the Mediterranean that same year. In November 2016, the V4 put forward an alternative migration plan. The buzzwords were “flexible solidarity” and “nation-state-centered approach". In a nutshell, they claimed that each member state “should be ready to contribute in different ways” also in other words by sending financial or technical support to the Southern Mediterranean States under migratory pressure, and not necessarily via mandatory relocation quotas. Their key point was that states must establish the policies and the relevant practices to deal with asylum seekers, without any interference or imposition put forward by the EU supra-national level. Finally, the icing on the cake came on the 24th of September 2020, when V4 members rejected the EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum.

V4’s U-Turn on asylum – at least in terms of rhetoric and willingness to show solidarity

In stark contrast to previous influxes of asylum-seekers, the Ukrainian refugee crisis is showing a different kind of solidarity among V4 members – at least for now. To be sure, this shift in responses to asylum seekers is part of a more general trend towards a remarkable U-turn in policy responses and discourses about refugees by many European political leaders – including those at the head of radical right anti-immigration parties, such as the V4.

The Polish Minister for the Interior, Kaminski, declared that the Polish borders are open to all Ukrainians, regardless of their legal status. The Prime Minister of Hungary, Victor Orbàn, further stated that “all Ukrainians fleeing from war will find a friend in the Hungarian State”. In spite of their previous state-centered and anti-supernationalist approach to migration management, the V4 did not pose any objection to the EU’s initiative of activating the 2001 Temporary Protection Directive which would grant refugees coming from Ukraine a residence permit, and access to education and the labour market. The activation of the Directive is in itself a remarkable turnaround in the European panorama since the European Union had indeed been in a state of deadlock for years over common action in the field of asylum.

At present, Slovakia and Hungary are already implementing such a Directive. The Polish and Hungarian governments have established several reception and information centers both at the borders and in several cities within their countries.

Although rhetoric and practice are changing, volunteers and NGOs from the field report that most of these centres are poorly organized and do not work efficiently.

But why?

Scholars have been debating for weeks about how to explain this U-turn, not specifically with regard to the V4 but from a more general perspective. Among the key drivers of more welcoming attitudes and policies towards people from Ukraine than those from the Middle East and Africa in the past year, are the fact that there is increased geographical proximity as well as perceptions of a greater cultural and ethnic similarities and that the compositions of fleeing flows differs from previous ones in which the predominance of Muslim males during the 2015 refugee crisis is in stark contrast to the Christian women and children who make up the majority of the refugees from Ukraine today. Some additional factors, however, need to be accounted for to understand the policy turnover with specific regard to the V4 and these are characterized by political motivations. We can plausibly argue that newly solidary V4 members especially Hungary and Poland, might hope to get away with their open challenges to EU law and the Western rule of law.

First, Poland and Hungary have committed several infringements of the rule of law at the national level in the field of civil rights and liberties. In December 2019 the Polish government approved a policy reform that strongly limited the independence of the judiciary power in Poland, subjecting it to stricter governmental control. As a response, in 2021, the European Court of Justice condemned Poland and requested a further reform to suppress the effect of the 2019 reform. Hungary is in the EC’s crosshairs too. Prime Minister Orbàn was repeatedly accused of curbing the rights of minorities in his country - both immigrants and the LGBTQ community. Based on the European Court of Justice’ ruling that complying with rule of law is a condition of enjoying membership of the EU, in February 2022, the EC froze Recovery Fund money for the two countries.

Second, the EU has highly criticized Polish authorities because of their violent pushbacks of remarkable numbers of Iraqi, Turkish Kurds and Syrian migrants from the Middle East who remained stuck at the borders between Poland and Belarus. This is in contrast to EU rules, which grant the chance to access the asylum process to everyone. In spite of criticism, the Polish authorities continue to ignore the demands of the European Court of Human Rights for the provision of assistance to people stuck at the border. Poland has also repeatedly refused the European Commission pushes for a Frontex deployment at its border with Belarus. As Belarus has suspended return agreements with the EU, people at the borders are caught in the middle, with no adequate humanitarian assistance. Will the Hungarian and Polish new “open arms” approach towards asylum seekers from Ukraine help them to regain an advantage in front of the Commission? It is still too early to tell, but both countries are already subtly working for it. Unsurprisingly, a few days following the outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis, some Polish members of the European Parliament had already explicitly claimed that “The European Commission should immediately cease any sanctions against Poland”.

What may this mean for the EU?

At this stage it is difficult to predict the future implications of the Ukrainian crisis on the overall EU asylum policy. On the one hand, it may create a new impetus for Europe to extend its security and defense mandate. Interestingly, building military capacity at EU level has been on the V4’s agenda for a long time. In their view, this is also strategically linked to the aim of strengthening the external dimension of migration management, in order to keep asylum seekers outside the EU. On the other hand, this crisis may give a fresh impetus to disputes over the EU migration and asylum policy. The V4, who until now have always rejected any quota-based redistribution mechanisms, may now start to need it to manage the growing flows of people coming to their countries. The UN estimates the number of asylum seekers from Ukraine will further increase over the coming weeks and these states are not equipped to handle such a volume of people. As a result, redistribution may turn to be the only plausible solution. Poland has just started to take the first steps in this direction. The Polish Ministry of Interior Kaminski appealed to the EU Commission for help in view of the increasing flow of refugees from Ukraine. The other V4 states may follow. Is this view too optimistic? The next events will tell us.

Tags

Citation

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license except for third-party materials or where otherwise noted.

How cities and regions are turning immigrants into citizens, whatever the central governments think

Verena Wisthaler

Verena Wisthaler

Young migrants in Euregio: identity through a blend of languages

Katharina Crepaz

Katharina Crepaz

Without citizenship, but citizens nevertheless

Johanna Mitterhofer

Johanna Mitterhofer