magazine_ Article

A gut feeling – how intestinal flora is changing with the times

The more modern our lifestyles, the fewer species live in our gut

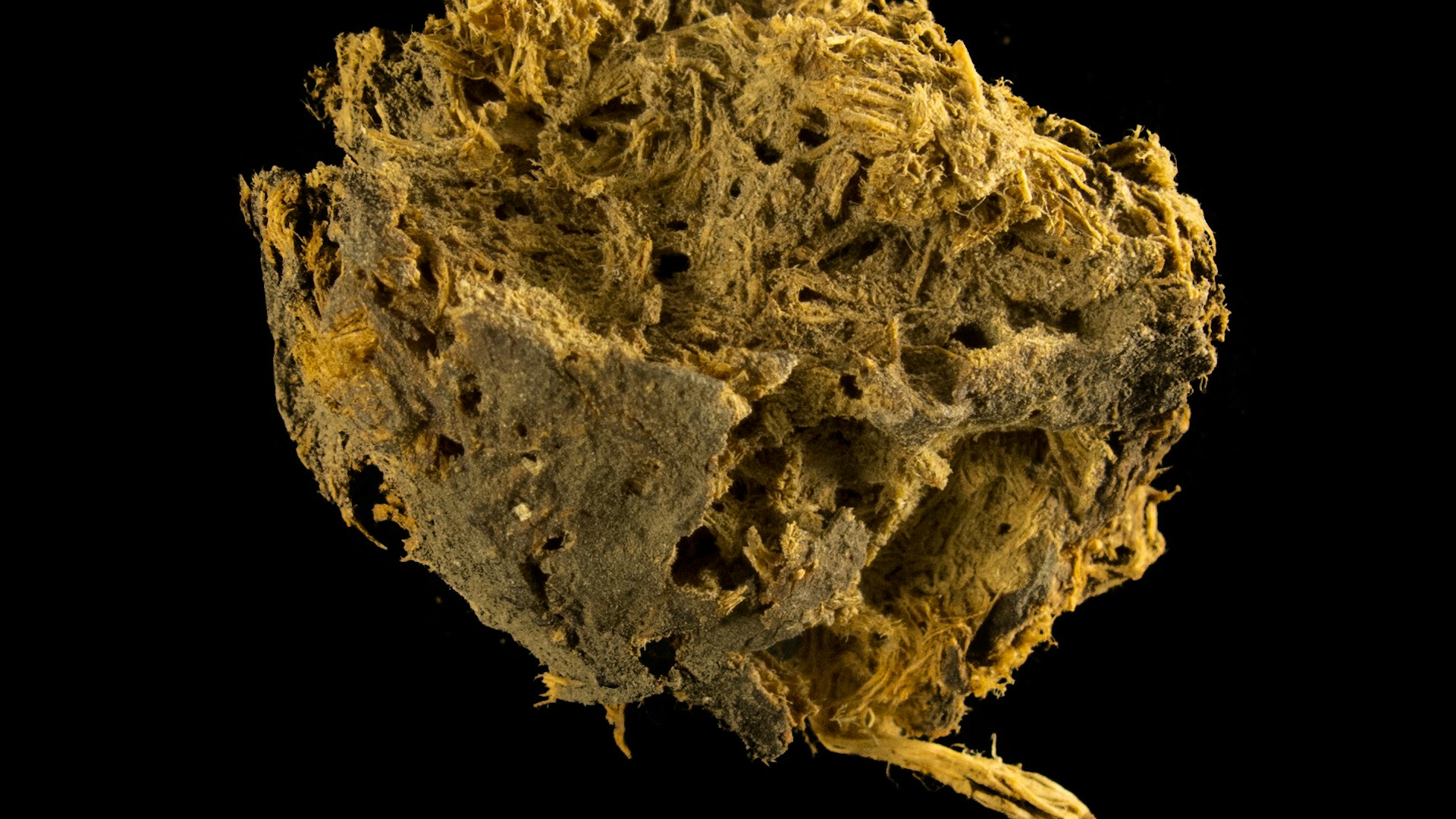

In 7th-century fecal material found in a cave in Mexico, Eurac Research experts were able to detect all four variants of prevotella copri. The intestinal bacterium is nearly extinct in industrial societies - if anything, it's found in our intestines in only one variation.

Credit: Eurac Research | Frank Maixner

Trillions of microorganisms live on and in humans, most of them in the gut. But our lifestyles are causing the diversity of this bacterial population to shrink dramatically - with far-reaching consequences to our health. Scientists around the world are doing research to better understand the microbiome. And the mummy experts from Eurac Research are also providing an important contribution.

Microbiologist Frank Maixner, an expert in uncovering the secrets of mummies and an authority on the world’s most famous iceman - Ötzi, is back from an unusual work mission. In a tunnel of the Hallstadt salt mines, he uncovered and unusual find…ancient excrement. "A gold mine!” in his own words.

"Salt was mined in Hallstadt over a period of almost 3,000 years, and, in case of need, the miners defecated in the gallery." He beams. In his laboratory at NOI Techpark, Maixner conducted initial experiments on the material he recovered: "It looks promising, the salt seems to have a very preservative effect."

Maixner's delight in fossilized feces has a specific reason. The coprolites, as they are called in technical jargon, can often reveal surprisingly precise indications about the intestinal flora of the person who produced them through the analysis of the ancient DNA which they contain.

In 7th-century fecal material found in a cave in Mexico, Eurac Research experts were able to detect all four variants of prevotella copri, an intestinal bacterium that helps break down complex vegetal aliments. The investigation was part of a large study in which Nicola Segata and Adrian Tett of the University of Trento analyzed the intestinal flora of 6,500 people from around the world. Prevotella copri, they found, is nearly extinct in industrial societies - if anything, it's found in our intestines in only one variation. In tribal communities in Ghana and Tanzania, however, the researchers found three variants - the same diversity that Maixner and colleague Albert Zink identified in Ötzi's stomach material, which they also examined for the study.

Prevotella copri is just one of thousands of bacterial species that live in our digestive tract, home to most of the trillions of microorganisms that colonize the human body. The central role this microbiome plays in our development and health has become increasingly clear in recent years: food processing, metabolism, immune defense, the state of our psyche - all of these aspects are influenced by the bacteria in our gut, with which we share a symbiotic relationship. One British researcher has called this relationship a "tango between humans and microbes," a tango danced which has been embraced for millions of years. But the lifestyle of western civilization seems to have broken something. Although we are only "at the beginning" of our understanding of the microbiome, as Maixner points out, countless studies, including those by researchers in Bolzano and Trento, show incontrovertibly that the living conditions of the industrialized world are associated with a dramatic depletion of the microbiome. The diversity of a person's gut flora does not depend on their ethnicity, or the continent they live on, but on what we commonly call "progress": the more modern our lifestyles, the fewer species live in our gut.

This loss is significant because a depleted microbiome has been linked to increased susceptibility to a variety of diseases, from allergies and asthma to autoimmune disorders, chronic gut inflammation, and obesity.

This has led some scientists to suspect that microbiome depletion may be a common cause for widespread disorders in our society - hence the immense interest in medical research.

Humans often forget that they are part of something greater than themselves

Frank Maixner

It seems that our lifestyle is destroying the biodiversity of our gut in the same way that it is destroying the biodiversity of the nature around us, and with the same serious consequence.: robbing us of important life support systems. "Humans often forget that they are part of something greater than themselves," expounds Maixner.

What amazed him about the results of the prevotella copri study was "how much was lost in such little time." The time from Ötzi to us, relative to human history, is just a blink of an eye; if you look at prevotella copri, however, the Iceman's gut flora was three times as diverse. Researchers have been able to discover this thanks to rapid advances in ancient DNA analysis. Thus, with their analysis of ancient samples, mummy experts are contributing important findings to a topical branch of research. "Meanwhile, we can show that the microbiome of indigenous populations still living in relative isolation actually represents a kind of original state, so it's suitable as a comparative value. And then we can track change, look back to a time when certain factors simply didn't exist yet."

What factors exactly? Science has already identified some: antibiotics, cesarean sections, chemical additives in our food and generally, a diet that has little in common with the diet of the past. Babies who are born by cesarean section and who therefore do not come into contact with their mother's vaginal secretions may be recognized years later because certain bacterial strains are missing from their microbiome altogether. Mice given low-fiber food had only half as many gut bacteria already even by the fourth generation. How to counteract the depletion has already been tested in some cases. "In Sweden, for example," says Maixner, who was there for an extended research stay, "they are experimenting with immediately rubbing c-section babies with the mother's vaginal secretion, collected earlier with a sponge."

But solutions aren't always easy to find. Because in the intestinal ecosystem, scientists are dealing with "a complexity that exceeds our imagination." Maixner goes on to say, "It's not just about the individual bacterial strains, but their interaction in neighborhoods and communities." In any case, science is still far from being able to define a "good" microbiome; the only thing that seems clear is that it can be very different. For example, the microbiome of those descended from generations of milk-drinking cattle ranchers is very different from that of populations that have lived primarily on fish for centuries. The behavior of a particular bacterium also depends on the conditions it encounters. Prevotella copri, for example, has been linked to a disease condition in some studies, while other studies indicate positive effects. The diet of the human host is thought to make a difference. In a major research project, an Israeli research team is trying to determine the right diet for individuals based on analyses of the microbiome to prevent or treat disease. "The gut microbiome is the barrier between us and our food," Maixner explains. "There's a very close connection, but we still don't know much about what it looks like in detail." Because the diet of the Hallstadt miners can be reconstructed relatively well, Maixner hopes to find interesting answers to this question with his study. And thus shed a little more light on the mysterious world in our stomachs.

This article was published on December 13rd 2019, in the weekly magazine Südtiroler Wirtschaftszeitung, with the title „Das Artensterben im Bauch”.