magazine_ Article

So, what’s a biobank actually for?

The most obvious answer is to preserve biological samples, but there’s much more to it than that.

How long can samples be stored in a biobank? Does one pay to store the samples or to use them? Who can access them? And how do geopolitics impact such facilities? Geneticist Alessandro De Grandi, head of the Eurac Research biobank has the answers.

Alessandro De Grandi’s smile widens as he places his badge on the little grey box and the lock opens. He opens the door wide, and there it is ̶ the biobank. To his right is a room containing large cylindrical tanks that emit occasional puffs of nitrogen like smoke which then encrusts the pipes with ice; opposite him, a room with 30 freezers and to the Geneticist’s left sit the tables and hoods where his colleagues prepare biological samples like blood and urine for storage.

De Grandi’s welcome is playful: “A biobank is forever!”

Situated in the basement of Bolzano’s General Hospital and a little difficult to find: a rather circuitous route through low-ceilinged neon-lit corridors will bring you to Eurac Research’s biobank. The facility definitely doesn’t take center stage but occupies an albeit more discreet space for a character upon which the research of today and tomorrow rests.

“We aren’t stamp collectors. My worry is the samples that have not yet been analyzed. I would like each one of them to be useful.”

Alessandro De Grandi, Genetist

“The timeline for our work is very long,” explains De Grandi, a geneticist from Bolzano who, after years of experience around the world, returned home and coordinated the creation of the biobank. “The oldest samples we keep here are from the MICROS study, which collected samples from around 1,500 people in the Vinschgau/Venosta valley in South Tyrol back in 2002. The CHRIS population study, in fact the large-scale evolution of MICROS, now has more than 13,000 participants. This actually means that we have around thirty years’ worth of data, and there will be other new initiatives that continue from here in the future. Having said that, samples can theoretically be stored and analyzed forever”.

Numbers from the Biobank

1.068.058

samples in storage

354

studies authorized to date

Biobanks for therapy and for research

Every major hospital has its own biobank where it stores blood for transfusions, bone marrow and stem cells for leukemia therapies, tissue for transplants and, in some cases, gametes for IVF. Bolzano’s hospital is no exception, and theirs is located adjacent to the one managed by Eurac Research. It is like a pharmacy that, instead of dispensing drugs, provides biological material that can be used for various medical treatments.

“In biobanks that are also intended for research, population biobanks for example, the value is not the sample itself, but the information that can be obtained from it,” De Grandi points out.

In the CHRIS study, 37.5 milliliters of blood is collected from each participant. The amount was calculated to be as minimally invasive as possible while still providing sufficient material for studies. Some of the blood is kept whole so that DNA can be extracted later. The rest is centrifuged to separate the different fractions that make up the blood.

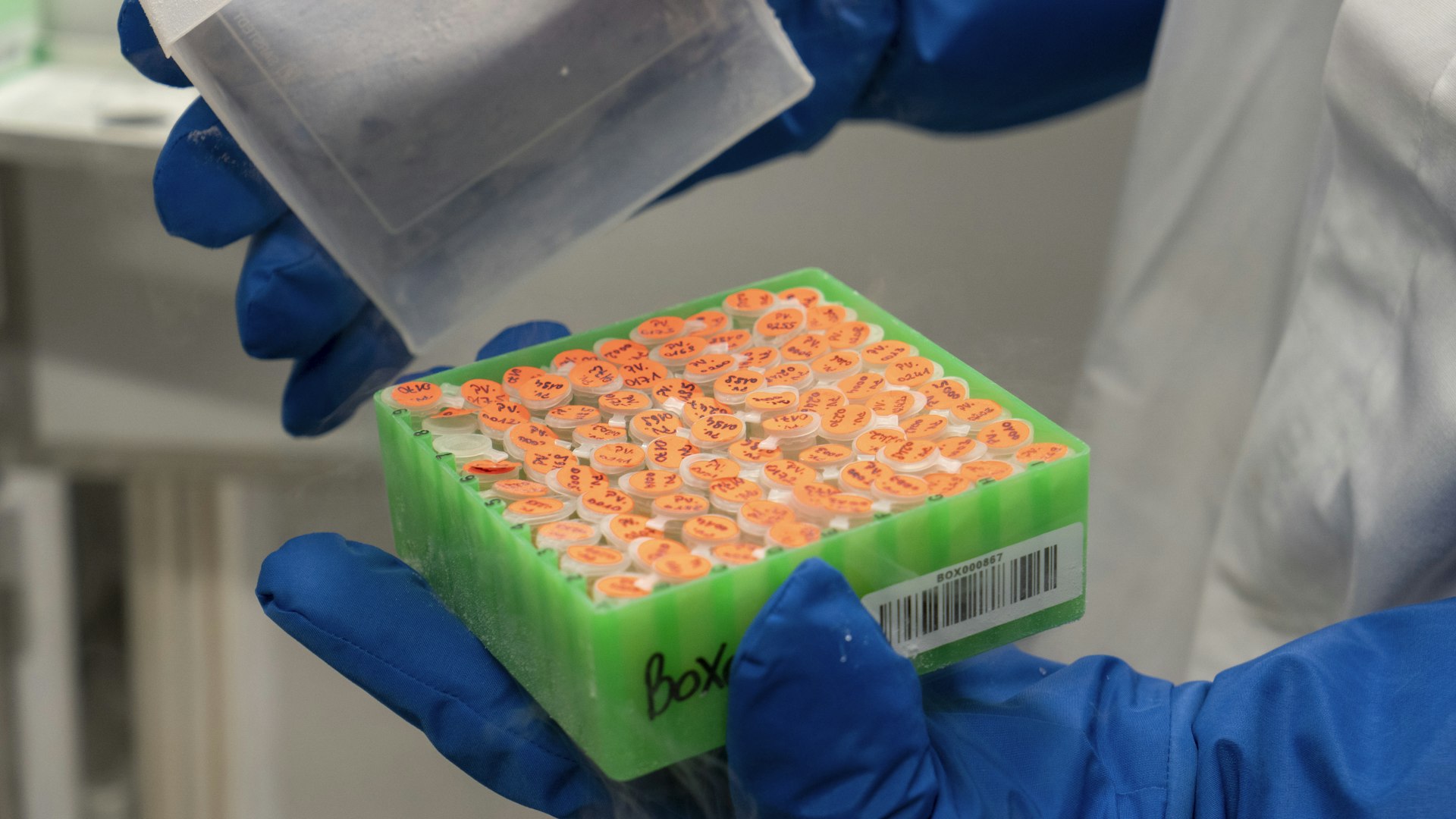

The separated blood fractions are then placed in the most suitable freezers: entire blood cells and white blood cells as well as platelets go into the tanks which have the lowest temperature: over -150 °C, red blood cells and plasma go into the freezers at a slightly higher temperature of around -80 °C. Urine samples also go here, about ten tubes per person. With a few hours of work and about €500 in costs, including staff expenses, all the materials that relate to one person are secured.

De Grandi is evidently proud of the huge effort that went into setting up the facility, which opened in 2015, and in creating the semi-automated process currently being used to organize the samples. But he is not entirely satisfied just yet.

“We aren’t stamp collectors,” he laughs. “My worry is the samples that have not yet been analyzed. I would like each one of them to be useful.”

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie Bortolotti

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie BortolottiIn Eurac Research’s biobank in Bolzano, there are five very low-temperature refrigerators. They contain whole blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. The temperature ranges from -80 to -197 °C and they are cooled with nitrogen. About 10,000 litres of nitrogen is needed every year for this.

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie Bortolotti

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie BortolottiEvery year, spring cleaning is also done in the biobank: tanks are checked and if there are any empty spaces left, the samples are redistributed in a more orderly manner.

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie Bortolotti

Credit: Eurac Research | Annelie BortolottiThe oldest samples stored in the Bolzano biobank are more than 20 years old and come from the epidemiological MICROS study, which collected samples from around 1,500 people from Vinschgau/Venosta in 2002.

A combination of data

The Eurac Research biobank is Open Source. Anyone, including internal working groups of course, can submit a research project to the Access Committee for ethical and practical evaluation. If it's accepted, only the funds are required.

“We can provide both data and samples, although with the actual samples we are more cautious because they are a finite resource. In these cases, we deliver the minimum sample to practices that have the best chance of achieving a result, both in terms of experience and collaboration, and in terms of financial resources,” explains De Grandi. “There have been past occasions where we have had to refuse requests if the study’s chances of success were very uncertain and therefore investing samples was too risky.”

So far, there have been 369 applications, with an approval rate of 96%.

“We can provide both data and samples, although with the actual samples we are more cautious because they are a finite resource.”

Alessandro De Grandi, Genetist

Eurac Research’s biobank is part of the European BBMRI-Eric consortium, which brings together almost 650 biobanks from 17 countries, plus about as many in Canada and the USA and about 140 in the UK.

“Our biobank is one of the few dedicated to pure research. And is undoubtedly the one that has the highest number of samples collected from a single site, the Vinschgau/Venosta valley,” explains De Grandi. This is an advantage because some environmental conditions are more homogeneous and family relationships can also be analyzed, but it’s not always enough.

In some cases, large numbers are needed to have statistical power and it is essential to join forces. As such, data from the Bolzano biobank has contributed to large international studies that sought to define which genetic factors influenced the severity of Covid-19 infections as well as to update the map of genetic regions associated with kidney function and to better understand chronic pain.

Collaboration has not always been so close. The first biobank came into being with the Framingham study, which in 1948, collected blood samples from the entire population of Framingham, a town in Massachusetts, USA to estimate the risks of cardiovascular disease. Then in the 1990s, epidemiological studies became increasingly popular, with the added factor of keeping some extra blood for possible further research. “I was working in Lyon in the early 2000s, at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and I remember that the biobanks were almost private entities and they were protected like real treasure,” De Grandi says with a smile. “Fortunately, the Open Source revolution followed and with it, significant openness and regulation.” Fortunate indeed, because collaboration although indispensable for advancing research, is not always easy to achieve.

Privacy and international geopolitics

In the Eurac Research biobank, attention to the protection of sensitive data may seem to verge on the obsessive, and quite rightly so. In addition to the procedures for informing and collecting informed consent from those who donate their samples, the repository is protected by a strict anonymization system. The samples stored in the freezers are marked with so called “2D codes” that allow the identity of the person to be traced in case of need. However, this can only be decrypted by several security steps. Furthermore, the research team even avoids using e-mails for communication on sensitive content.

Once the studies that have used data from the biobank have been concluded, the access committee that had authorized them reviews the publications in advance: it does not want to evaluate the results, but to oversee the ethical standard of the work, since the biobank is also responsible for secondary data.

The samples stored in the freezers are marked with so called “2D codes” that allow the identity of the person to be traced in case of need. However, this can only be decrypted by several security steps.

Geopolitics affects the international collaborations.

For instance, exchanges with the United States were not possible until this summer because there is no clear law there that limits the links between data and subjects, a stark contrast to the Italian privacy guarantor which is particularly restrictive. And though an agreement has been in force since July 2023, it is still being debated.

The United States, as well as other countries, have repeatedly been accused of predatory attitudes towards minority populations or poor countries having allegedly hoarded biological samples and data and employing protocols that are not entirely transparent and which is referred to as biocolonialism.

Often lucrative offers for laboratory services such as genome sequencing arrive also in Bolzano from China but are declined because the costs of less than solid guarantees on the handling of personal data simply are not worth the price.

“We cannot rely solely on trust between those involved in research, we need clear rules,” concludes De Grandi. “But exchanges are not an option, they are a necessity. What does the future hold? I see a decisive role for biobanks in the study of oncogenes, the genes associated with cancer.”