magazine_ Article

Drones for science

Remotely piloted aircraft are changing scientific research

From monitoring natural hazards and assisting mountain rescues to applications in agriculture and forestry science. Drones are proving to be increasingly valuable allies for researchers, professionals and administrative departments. Drones acquire more detailed data than satellites and can provide measurements that would be demanding if taken manually. In recent years the remotely piloted aircraft have been tested in a range of diverse and challenging situations with the latest tests being conducted at an altitude of 9,000 m.a.s.l.

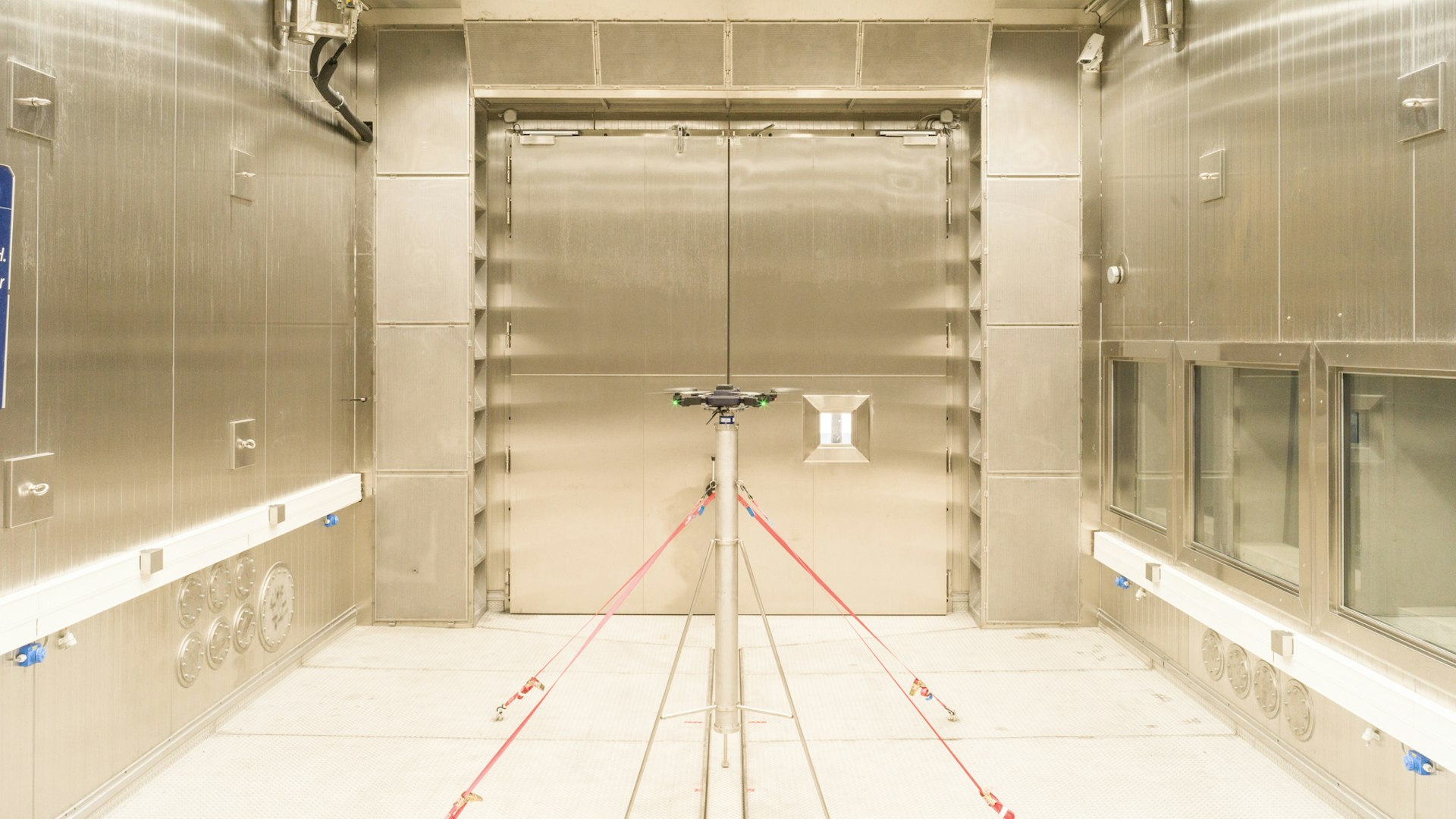

Recently in terraXcube’s Large Cube, a very special test took place: two large drones loaded with various heavy equipment were flown inside the largest test area of the Extreme Climate Simulation Center’s chambers.

While the pilot's skill in maneuvering the drones in an enclosed space was certainly noteworthy, what made the experiment interesting was something else: the chamber had been artificially raised to an altitude of nearly 9,000 m.a.s.l. ̶ well in excess of the altitude of our planet’s highest peaks. It was the first time that the free flight of a drone had been tested inside the terraXcube at these simulated altitudes.

The higher the altitude, the thinner the air. And, thin air results in a decrease of the drone’s thrust capacity. Owing to this, it’s necessary to test the effectiveness of the engines ̶ especially when loaded with equipment which on this occasion, reached up to 4 kilograms.

The tests that took place in the terraXcube were conducted for Mavtech, a drone manufacturer based at the NOI Techpark in Bolzano, Italy. The aim of the trial was to understand the effectiveness of two new drone models intended for use in the Alpine environment ̶ a complex one, not only because of the air being thinner at altitude, but also because of its extreme climates and frequent weather. In the future, the types of drone tested in the terraXcube will go on to be used in these alpine environment in a variety of applications including landslide monitoring.

Natural hazards - a birds eye view

For more than a decade, a research team from the Institute for Earth Observation has been studying the evolution of a slowly but steadily moving landslide in Corvara by using three state-of-the-art monitoring stations, ground measurements and satellite data. By analyzing the different monitoring systems simultaneously over the years, the team has not only gained a detailed picture of the landslide but, more importantly, has also been able to compare the different monitoring and data acquisition methods, highlighting the advantages and limitations of each.

Integrating Different Methods for Landslide Monitoring: The Lemonade Project

This is precisely why in Corvara, under the aegis of the Blueslemon project, a new method of landslide data acquisition will be tested using drones and the data gathered can go on to be used on a larger scale to monitor unstable terrain in the future.

Drones on the hunt, for beacons

The plan is for drones flying independently over the landslide to “check” whether certain points on the ground have moved . This is done by using beacons, very small devices that despite consuming very little energy still manage to send a signal to an optical reader that passes over a certain area. The optical reader is mounted on the drone, which, as it flies over the landslide, “reads/recognizes/records” the beacons and through its GPS tracking system determines their exact location. In subsequent flights that take place over the next days, weeks or even months, the drone tracks the position of all the beacons again calculating whether and by how much they have moved. In this way, the research team is able to observe the landslide’s displacement.

"There are so many ways drones can help acquire useful data, it all just depends on the instrumentation they carry."

Abraham Mejia Aguilar, monitoring expert at Eurac Research's Center for Sensing Solutions.

A similar data acquisition strategy - again with drones as protagonists - was also tested by Eurac Research researchers in a context very different from the Corvara landslide: the Lazaun rock glacier. Glaciers of this type are composed of a mass of rock debris mixed with ice and can signal the presence of permafrost. These glaciers usually move just a few meters each year, but thawing permafrost could change this.

On the Lazaun rock glacier in the Senales Valley, researchers from Eurac Research are combining the use of state-of-the-art satellite imagery and other types of measurements, including drones. In Corvara, the use of drones was also explored in another way: the drones were not sent out to hunt for beacons, but for visible, shiny objects called corner reflectors that can be detected by camera. “The logic is the same however: the drone detects the object and consequently determines its exact location through its GPS system. In this case, it is not the beacon that transmits information to the reader positioned on the drone, but an optical camera that reads the terrain that when it finds the reflective object, records its position," explains Abraham Mejia Aguilar, a multiscale monitoring expert at Eurac Research's Center for Sensing Solutions.

Drones, science and more…

In these test areas, efforts are being made to understand which types of monitoring are most effective and which would work best if combined. So far, drone-supported monitoring is one of the most promising. “The use of drones could replace - at least in part - the manual measurements that have to be carried out by individuals on behalf of administrations and which are often quite challenging to take," explains Roberto Monsorno, head of the Eurac Research Center for Sensing Solutions. “In South Tyrol, for example, experts from the Geology Office have to use ropes to climb walls in order to detect possible hazards.” Some of this data acquisition could be carried out by drones that, in automatic flight, detect the movement of beacons placed on the rocks instead.

"Compared to satellite images, those captured by drones display much higher accuracy and detail”

Roberto Monsorno, head of the Eurac Research's Center for Sensing Solutions

Land monitoring and natural disaster prevention, however, are just two of the areas where the use of remotely piloted aircraft has been tested over the past decade. “It all depends on the instrumentation that is used,” explains Abraham Mejia Aguilar, "for example, by combining particular cameras and spectroscopic analysis, drones become valuable tools to understand whether a forest or an apple orchard is healthy.” Using the images captured by drones, spectroscopy can help assess whether a plant is healthy or diseased. The data gathered can then be confirmed through random ground-based measurements.

“Compared to satellite images, those captured by drones display much higher accuracy and detail, even at the level of an individual plant.” In recent years, drones have proved highly useful in acquiring data to study the presence of fungi and bacteria in crops in South Tyrol, assess the impact of the processionary moths in forests, and monitor the spread of apple broom, one of the most dangerous diseases that affect apple cultivation. In the future, drones could be used to assess the spread of the bark beetles that attack spruce trees and that are also increasingly present in areas affected by Storm Vaia – all before damage is visible to the naked eye. There’s more.

The future of drones

The two large drones recently tested inside the terraXcube could also be used in a decidedly different field: mountain rescue. In 2021’s Start project, Eurac Research and the South Tyrolean Mountain Rescue team tested the use of drones for emergency operations in the Bletterbach Gorge. The goal was to find out whether drones were able to help in locating and treating injured people in remote and difficult to access sites.

For the project, a normal and a thermal imaging camera and a transmitter capable of tracking the cell phone of the person to be rescued were mounted on the drone. Once the person was located, the drone would also drop a first aid kit on the ground.

One of the first tests for emergency operations using drones. The test took place in 2021 as part of the Start project, in the Bletterbach Gorge.

One of the first tests for emergency operations using drones. The test took place in 2021 as part of the Start project, in the Bletterbach Gorge.Video: Eurac Research

In the deep dolomite gorge of Bletterbach, researchers were also engaged in checking another key aspect: the transmission of data from the drone to the ground rescue team, which was transmitted to the pilot via LoRaWAN protocol, technology that uses little energy and which is able to transmit over great distances.

“It is precisely in the transmission of data that we expect to see the most noticeable improvements in the coming years, thanks to research and technological advances,” explains Roberto Monsorno. “In the context of mountain rescue, drones need not only to operate with as little energy as possible, they also need to be able to transmit a large amount of important data in real-time-or near real-time.”

However, the use of rescue drones may face challenges in the coming years. On the one hand, work is being done on improving performance: keeping drones up and running for a longer time while using less energy than at present. On the other, efforts are being made to provide better tracking capabilities and greater decision autonomy: drones should be able to “pick and choose” when the time is right to send information the moment they come across victims, anomalies, or risky situations.