magazine_ Article

Fighting over water

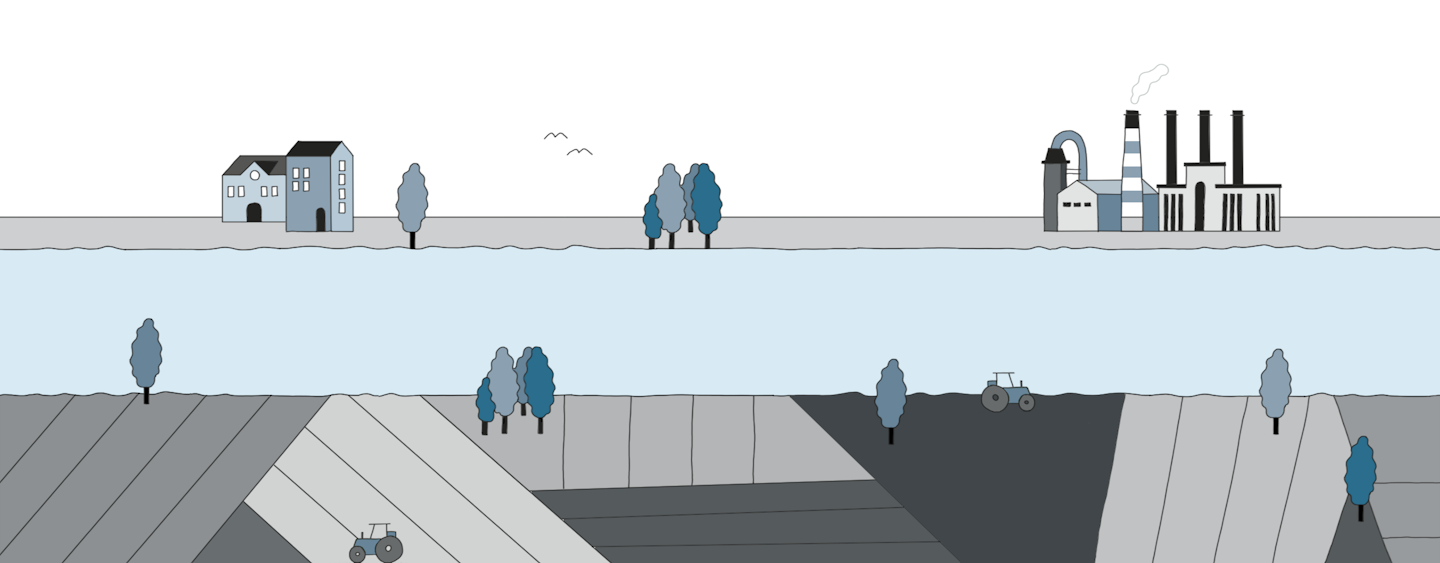

Graphic article – How the water resource of a river is used and what conflicts may arise among those who benefit from it.

Those who live, work, or vacation along the course of a river use its water in many ways. The timing and quantities consumed vary, but each use has consequences for all the others. This can lead to possible conflicts, varying in intensity, that, in times of drought, escalate to the point of becoming an emergency. From the source to the mouth, we follow the course of a medium – or large-sized alpine river – such as the Adige River – to discover how the water is used and how conflicts arise between the different categories of users.

The source and the first stretch of the river

Water supply and bottling. Water at the source can be captured for public supply, then directed to the aqueduct through pumping systems and gravity, or used for bottling.

Artificial snowmaking. In the early sections of the river, water use for human activities is usually limited. One possible use is for artificial snowmaking, which either uses artificial rainwater reservoirs at high altitudes or takes water from the river.

The upper course of the river

Tourism. The river’s course is a valuable asset that shapes the landscape and contributes to its aesthetic appeal. It is also a hub for tourist activities such as rafting, canyoning, or simply hiking. These activities represent a passive use of the river, meaning they do not consume its water, but are heavily dependent on the river’s ecological health.

Hydroelectric power plant. Large-scale hydroelectric plants are among the main water consumers throughout the river’s course. There are various methods to generate hydroelectric energy and several types of plants, but this usage involves a unique dynamic: water is only temporarily "diverted" from the river's natural flow, channeled through turbines to produce energy, and then released back into the river further downstream. The timing and methods of this release follow specific regulations, often dictated by the logic of the electricity market.

Valley agriculture in mountainous areas. In mountainous regions, valley agriculture often focuses on highly specialized crops, such as apple orchards and vineyards. Irrigation in these cases is also specialized; for example, drip irrigation systems are used, which consume minimal amounts of water.

Frost prevention irrigation. A more intensive use of water by agriculture in the upper course of the river occurs in early spring. When nighttime temperatures are still low in apple orchards, farmers spray water on young leaves and flowers to create a protective ice layer. This ice keeps the internal temperature constant, preventing frost damage. However, this method requires significant amounts of water, especially since multiple farms often activate overhead sprinkler systems simultaneously.

Fish farming and fishing. Those who farm or fish in the river do not directly consume water. However, these activities are influenced by the river’s water levels. Many people in this category of users have a high degree of ecological awareness and are often the first to notice changes in the river ecosystem.

A potential conflict: upstream of hydroelectric plants

A conflict arises when an agricultural business takes water directly from an artificial lake that is also used for hydroelectric power generation. During drought conditions, the water level in the lake is low, and farmers require more water for irrigation. However, extracting the water becomes more costly, as it needs to be pumped from the lower levels of the reservoir. Shared management plans mediate the needs of the farmers with those of the hydroelectric plant for energy production.

A potential conflict: downstream of hydroelectric plants

Mountain agriculture and the hydroelectric sector operate on different schedules that do not always align, which can lead to small, localized conflicts that only emerge during certain periods or at specific times of the day.

The hydroelectric plant follows the logic of the energy market: when there is a higher demand for electricity and prices rise (such as in the morning), the plants begin to operate. The water flowing through the turbines is immediately released downstream of the facility. But is this really the time when this water is also needed by the nearby agricultural businesses? Not always.

The use of irrigation methods that consume little water helps keep potential conflicts very localized.

The lower course of the river

Industry. The industry utilizes water in various ways, such as raw materials, for cooling machinery, or for washing equipment. The amount of water used depends on the type of activity and the efficiency of the technologies in place.

Plain agriculture. Some typical crops of the plains – such as corn, soybeans, and rice – do not permit drip irrigation. The fields are large-scale, and water is dispersed using sprinkler irrigation. While drip irrigation typically achieves about 90% efficiency, sprinkler irrigation in the plains is only about 50% efficient, as much of the water evaporates or isn’t distributed precisely where needed.

A possible conflict: hydroelectric plants upstream and extensive agriculture in the plain

Hydroelectric plants upstream and extensive agriculture downstream are among the users that can often come into conflict due to their high levels of water consumption, especially during periods of prolonged drought. In these situations, associations representing agriculture downstream may request a higher water release from artificial lakes. On the other hand, upstream users may criticize the inefficiency with which water is used. Cross-regional forums and drought observatories aim to find shared solutions for addressing both immediate and long-term challenges.

The mouth of the river

City use. In cities, both residents and tourists use the river’s water. The amount of water extracted – either from the source or along its course – is calculated to meet the needs of the entire population. In smaller cities or towns with significant tourist traffic, water demand can increase by up to five times during peak seasons.

Natural preservation. Areas like river mouths are often of high natural and touristic importance. For example, deltas represent unique ecosystems with fragile balances, where specialized flora and fauna can be observed.

Saltwater intrusion: the conflict between upstream and downstream users.

The effects of water scarcity are most visible at the river’s mouth. Those who live, work, or visit these areas experience the consequences of how the water has been used and the policies implemented along the river’s entire course. Residents, businesses, and municipalities at the mouth may find themselves in conflict with users further upstream.

One of the most evident consequences is saltwater intrusion. When the river’s flow decreases, seawater pushes up the river, increasing the concentration of salt in both the water and the surrounding soil. Salt endangers the balance of ecosystems, damages crops, and makes groundwater undrinkable. This issue can be mitigated by constructing anti-salinity barriers at the river’s mouth and releasing more water from upstream reservoirs. The question remains: who should act first?

Technical documentation

Technical documentationPolicies and tools for water availability trends: The NEXOGENESIS Project

NEXOGENESIS is a large European project involving 20 partners from 11 European countries and South Africa. Its goal is to develop policies and tools to manage water resources effectively and prevent conflicts among users. Eurac Research is responsible for the Adige River Basin case study. The research team is developing mathematical models that investigate future trends in water availability and demand. Within the project, discussion forums and dialogues are organized among the different users of the Adige River Basin, alongside qualitative interviews. The project is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.